Written by Sidra Tul Muntaha - Editor: Anastasia Eginoglou

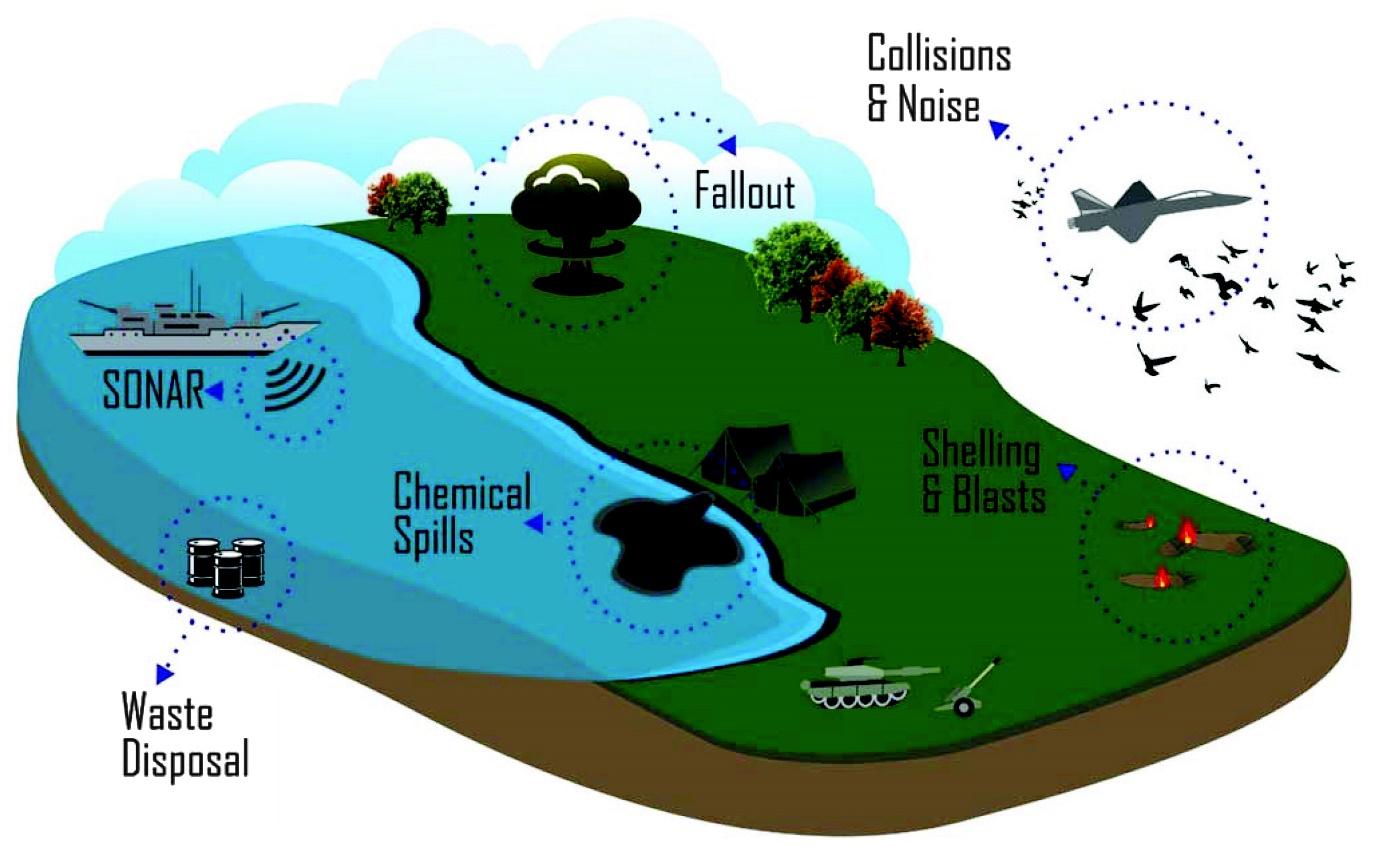

In the 21st century, the world has progressed technologically, but it has also become increasingly weaponised [1]. The severity of war damage depends on the weapons used and the military strategies [2]. Despite the devastating generational and ecological consequences observed in Hiroshima and Nagasaki - where nuclear attacks caused long-term genetic and food-web disruptions - wars continue to devastate both human and environmental systems. Recently, we have seen armed conflicts turn into war zones between Ukraine and Russia [3] and Palestine and Israel. These wars have affected human lives while also reshaping global geopolitical, social, economic, and food security [4, 5, 6]. The effects of war have been so extensive and far-reaching [7] that the destruction of habitats, species displacement, and ecosystem collapse have often been overlooked [5]. The effects are mainly negative and have either a direct or indirect impact on the ecosystem [6, 8, 9]. These wars have drawn in global involvement, heightening tensions and increasing the risk of nuclear conflict, which could have catastrophic environmental consequences [10].

Every layer of atmospheric stratification is affected and its impact can last for centuries. Studies provided evidence of various environmental impacts, including greenhouse gas emissions, deforestation, and wildfire outbreaks. Wars also contribute to habitat destruction, wildlife displacement, soil degradation, and water pollution. Additionally, they reduce pollination, limit water availability, and degrade fertile soil. These impacts have indirect consequences as well [5, 11, 12], such as deforestation increasing air pollution, soil degradation lowering food production, and lack of water and water impurity impacting habitat mortality. Not to forget, the ecological imbalance has impacted human health as well, placing humans at huge risk due to exposure to unhygienic sanitary conditions. War also leads to the destruction of social, cultural, and architectural heritage [5, 12].

This article explores the often-overlooked environmental consequences of war, particularly its impact on biodiversity, and highlights the urgent need for global intervention to mitigate these effects.

Natural resources have suffered due to wars in the past, for example, the Tigray region of Ethiopia [13]. Currently, the war in Ukraine requires urgent attention regarding the impact of warfare on natural resources [14]. The ongoing conflict in Ukraine has raised concerns over potential radiation leaks due to its proximity to the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant and Chernobyl, both of which have been targeted during the war [3, 5].

In Syria, the annual water scarcity index reduced from ~760 m3/capita during pre-war to less than 500 m3/capita during wartime [15]. Even after 10 years of war, the drinking water reserves were reduced by 40% [16].

Since 1967, Israel has controlled water resources in the Occupied West Bank, restricting Palestinian access while increasing its own usage [17]. Food insecurity, water shortage, and global warming due to wars caused by political instability have thrown Palestine under great risk to human lives and endangered or lost different biodiversity across the ecosystem. Deforestation is one of the consequences of the war in Palestine that leads to lower carbon sequestration, leading to global warming. From 2001-2003, 1.1 million trees were uprooted in the Occupied Palestine Territories by Israel alone [18]. These long-troubled impacts will have catastrophic geopolitical conflicts that will continue to accelerate climate change [19].

Civil wars can also tear down law and order with increased availability of ammunition and rifles, especially in war zones areas like Angola. This widespread ammunition led to overhunting that depleted 77% of all mammal species in the area. However, the decline was not reversed even after the war ended [20]. The depletion of mammals leads to the disruption of ecosystem linkages between necromass, predators, energy and nutrients transfer [21]. Furthermore, there is evidence of an increased risk of zoonotic viruses and diseases from the close phylogenetic relationship between humans and wildlife [22].

War-torn Afghanistan has exploited biodiversity unsustainability either due to need or greed, where natural resources are looted and endangered species are looted, killed or trafficked, disturbing the ecosystem and food web [3].

War disrupts ecosystems in multiple ways, from the direct destruction of habitats to long-term environmental degradation. The following sections outline the major effects of warfare on biodiversity, showing how these impacts are interlinked.

Habitat Destruction and Wildlife Displacement

Wars lead to extensive habitat destruction through bombings, deforestation, and infrastructure damage. The excavation of trenches, tunnel constructions, and heavy military vehicles degrade soil, making it unsuitable for plant and animal life [3, 5, 11]. Large-scale destruction forces wildlife to migrate to human-populated areas, increasing the risk of human- wildlife conflict or leading to species extinction due to resource shortages [12]. Moreover, activities of huge-sized military vehicles and air force bombardments have been linked to the hitting and killing of wildlife [23].

Deforestation and Carbon Emissions

Military activities, including land clearing for bases, fuel supply routes, and training grounds, contribute to large-scale deforestation that disrupts the delicate balance of the ecosystem [12]. Even the movement of heavy vehicles damages soil which destroys the survival and establishment of flora and fauna [3].

Additionally, wildfires caused by bombings and deforestation increase greenhouse gas emissions, exacerbating global warming.

Chemical Pollution and Toxic Contamination

Military operations release harmful chemicals into the air, soil, and water. Explosives, heavy metals, and toxic residues from warfare lead to bioaccumulation in wildlife, affecting species at multiple levels of the food chain [23]. Uranium toxicity, for example, disrupts genetic structures, causes developmental deformities, and alters behaviour in mammals, reptiles, and aquatic life [24]. Birds consuming metal shell fragments also suffer from lead poisoning, leading to population decline [25].

Furthermore, landmines explosion disrupts ecosystems in many ways, such as by causing soil contamination that destroys vegetation and water flow [26, 27].

Water Scarcity and Pollution

Armed conflicts severely impact freshwater availability. The contamination of ecosystems through toxic residues and heavy metals not only affects wildlife but also leads to severe water pollution. Armed conflicts exacerbate water shortages by destroying critical infrastructure and disrupting natural water cycles [15, 28]. Moreover, there is a shortage of staff and a lack of treatment capacity [29]. The accessibility of water is restricted, especially in active war zones, such that the ground water is not safe to drink [15, 30]. Therefore, there is increased reliance on rainwater even by humans as treatment of water is expensive and there is lesser water available due to infrastructure and electricity constraints [30]. Even collected rainwater and run-off are often contaminated due to wastewater leakages and surface run-off pollution [15].

Food Insecurity and Agricultural Damage

Warfare reduces food production by contaminating soil, limiting irrigation access, and destroying farmlands. Agricultural land is often repurposed for military bases, and conflicts over water sources further disrupt food supply chains. Additionally, in war zones where wastewater is reused in agriculture, soil fertility declines, leading to lower crop yields and increased reliance on expensive food imports [12, 15, 18].

Sound Pollution

War-related noise pollution disrupts animal communication, migration, and survival patterns. Sonar waves from naval warfare affect marine mammals, leading to increased whale mortality due to auditory damage [10]. Similarly, aircraft and explosions impact terrestrial wildlife, causing stress, disorientation, and reduced reproductive success [23].

Beyond conventional warfare, the threat of nuclear war presents an even greater danger to biodiversity, with long-term and potentially irreversible effects. The detonation of nuclear weapons not only results in immediate destruction but also triggers long-term ecological damage, including widespread habitat loss, genetic mutations, and disruptions to entire ecosystems. Even adjacent forests and vegetation areas are affected through generations, causing wildfire spread that disturbs the nearing habitat and ecosystem as well.

Marine mammals and diving birds also experience lung damage and high mortality rates.

Radioactive exposure causes chronic impacts on animals along with the human population, such as neoplasia, irregular chromosomal development and genetic aberrations that reduce life expectancy and survival chances [23]. More so, genetic structure is altered [31].

The cumulative impact of war on biodiversity is not just immediate but persists for generations, affecting ecosystems, human health, and climate stability. Given the severity of these effects, urgent collaborative action is necessary to prevent further environmental devastation. If current conflicts escalate into a larger global war, biodiversity loss and environmental degradation will reach unprecedented levels, with consequences that may be irreversible [5]. It is seen that military leaders have little to no interest in ecological impacts where even after the war, restoration activities are seldom based on the ecosystem protection [32]. There is a need for an urgent multifaced and holistic approach that requires engagement between the stakeholders and policymakers to conserve the negative impacts on the biodiversity in the warzone areas [6, 12] where efforts are needed to stop the wars. Policy interventions and dialogues are required where lasting peace and security are prioritised while incorporating ecological science with military planning, conservation, rehabilitation and recovery efforts and services [7, 12]. There is a need to think of ecosystem-based approaches as recognizing the interdependency of environmental challenges with human wellbeing [11, 12] for the development of sustainable agriculture, fisheries and forestry to promote health and resilience [11].

Nature knows no political borders; it belongs to all of us. As silent victims of war, ecosystems bear wounds that take decades to heal. It is our collective responsibility to ensure that future generations inherit a planet where peace and biodiversity coexist [3]. Therefore, let’s all collaborate on a humanitarian basis to prioritize well-being for the planet and future generations alike.

References:

[1] Lujala, P. (2010). The spoils of nature: Armed civil conflict and rebel access to natural resources. Journal of peace research, 47(1), 15-28.

[2] Hupy, J. P. (2006). The long‐term effects of explosive munitions on the WWI battlefield surface of Verdun, France. Scottish Geographical Journal, 122(3), 167-184.

[3] Hulme, K. (2022). Using International Environmental Law to enhance biodiversity and nature conservation during armed conflict. Journal of International Criminal Justice, 20(5), 1155-1190.

[4] Sousa, Ronaldo, et al. "The cost of war for biodiversity: a potential ecocide in Ukraine." Frontiers in Ecology & the Environment 20.7 (2022).

[5] Pereira, Paulo, et al. "Russian-Ukrainian war impacts the total environment." Science of The Total Environment 837 (2022): 155865.

[6] Hanson, T. (2018). Biodiversity conservation and armed conflict: a warfare ecology perspective. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1429(1), 50-65.

[7] Machlis, G. E., & Hanson, T. (2008). Warfare ecology. BioScience, 58(8), 729-736.

[8] Coppock, R. W., & Dziwenka, M. M. (2020). Threats to wildlife by chemical and warfare agents. In Handbook of toxicology of chemical warfare agents (pp. 1077-1087). Academic Press.

[9] McNeely, J. A. (2003). Conserving forest biodiversity in times of violent conflict. Oryx, 37(2), 142-152.

[10] Rist, L., Norström, A., & Queiroz, C. (2024). Biodiversity, peace and conflict: understanding the connections. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 68, 101431.

[11] Bhardwaj, A., & Parveen, H. (2024). War and the Environment: The Ecological Consequences of Armed Conflict. The Academic-International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research, 2(9), 702-717.

[12] Ahmad, M., Sheikh, B. A., & Sheikh, A. A. (2022). The Environmental Fallout Of The Israel-Palestine Conflict: A Deep Dive Into The Ecological Impact Of Ongoing Hostilities. Journal of Survey in Fisheries Sciences, 8(3), 624-630.

[13] Jacobs, M. J., & Schloeder, C. A. (2001). Impacts of conflict on biodiversity and protected areas in Ethiopia. Washington, DC: Biodiversity support program.

[14] Grimes, E. S., Kneer, M. L., & Berkowitz, J. F. (2024). Military activity and wetland‐dependent wildlife: A warfare ecology perspective. Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management, 20(6), 2153-2161.

[15] Faour, G., & Fayad, A. (2014). Water environment in the coastal basins of Syria-assessing the impacts of the war. Environmental Processes, 1(4), 533-552.

[16] Crisis, S. W. (2023). Up to 40% less drinking water after 10 years of war.(nd). ReliefWeb. Accessed September, 13.

[17] Salem, H. S., & Isaac, J. (2007, November). Water agreements between Israel and Palestine and the region’s water argumentations between policies, anxieties and sustainable development. In Proceedings of Green Wars Conference: Environment between Conflict and Cooperation in the Middle East and North Africa. Middle East Office of the Heinrich Boell Foundation, Ramallah and Amman-Palestine and Jordan.

[18] Salem, H. S., Jerath, N., Booj, R., & Singh, G. (2010). Impacts of climate change on biodiversity and food security in Palestine. Climate change, biodiversity and food security in the south Asian region.

[19] Isaac, J., & Gasteyer, S. (1995). The issue of biodiversity in Palestine. Applied Research Institute-Jerusalem, Palestine, 1, 1-15.

[20] Braga-Pereira, F., Peres, C. A., Campos-Silva, J. V., Santos, C. V. D., & Alves, R. R. N. (2020). Warfare-induced mammal population declines in Southwestern Africa are mediated by species life history, habitat type and hunter preferences. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 15428.

[21] McCauley, D. J., Young, H. S., Dunbar, R. B., Estes, J. A., Semmens, B. X., & Micheli, F. (2012). Assessing the effects of large mobile predators on ecosystem connectivity. Ecological Applications, 22(6), 1711-1717.

[22] Childs, J. E., Richt, J. A., & Mackenzie, J. S. (2007). Introduction: conceptualizing and partitioning the emergence process of zoonotic viruses from wildlife to humans. Wildlife and emerging zoonotic diseases: the biology, circumstances and consequences of cross-species transmission, 1-31.

[23] Michael J. Lawrence, Holly L.J. Stemberger, Aaron J. Zolderdo, Daniel P. Struthers, and Steven J. Cooke. 2015. The effects of modern war and military activities on biodiversity and the environment. Environmental Reviews. 23(4): 443-460. https://doi.org/10.1139/er-2015-0039

[24] Briner, W. (2010). The toxicity of depleted uranium. International journal of environmental research and public health, 7(1), 303-313.

[25] Fisher, I. J., Pain, D. J., & Thomas, V. G. (2006). A review of lead poisoning from ammunition sources in terrestrial birds. Biological conservation, 131(3), 421-432.

[26] Austin, J. E., & Bruch, C. E. (Eds.). (2000). The environmental consequences of war: Legal, economic, and scientific perspectives. Cambridge University Press.

[27] Berhe, A. A. (2007). The contribution of landmines to land degradation. Land Degradation & Development, 18(1), 1-15.

[28] Schillinger, J., Özerol, G., & Heldeweg, M. (2022). A social-ecological systems perspective on the impacts of armed conflict on water resources management: Case studies from the Middle East. Geoforum, 133, 101-116.

[29] Zeitoun, M., Elaydi, H., Dross, J. P., Talhami, M., de Pinho‐Oliveira, E., & Cordoba, J. (2017). Urban warfare ecology: A study of water supply in Basrah. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41(6), 904-925.

[30] Özerol, G., & Schillinger, J. (2024). Water Management and Armed Conflict. In Elgar Encyclopedia of Water Policy, Economics and Management (pp. 340-344). Edward Elgar Publishing

[31] Theodorakis, C. W., & Shugart, L. R. (1997). Genetic ecotoxicology II: population genetic structure in mosquitofish exposed in situ to radionuclides. Ecotoxicology, 6, 335-354.

[32] Meaza, H., Ghebreyohannes, T., Nyssen, J., Tesfamariam, Z., Demissie, B., Poesen, J., ... & Vanmaercke, M. (2024). Managing the environmental impacts of war: What can be learned from conflict-vulnerable communities?. Science of the total environment, 171974.